hung parliament

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

English[edit]

Etymology[edit]

From the fact that the work of such a parliament is often suspended because no majority of the Members of Parliament can be obtained to enact legislation or to pass resolutions.

Pronunciation[edit]

- (Received Pronunciation) IPA(key): /hʌŋ ˈpɑːləmənt/

- (General American) IPA(key): /hʌŋ ˈpɑɹləmənt/

Audio (AU) (file) - Hyphenation: hung par‧lia‧ment

Noun[edit]

hung parliament (plural hung parliaments)

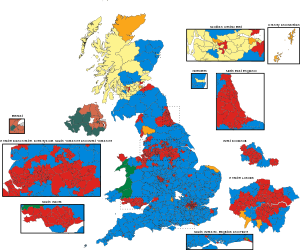

- (government, politics) A parliament in which no single political party has an outright majority.

- 1995, Vernon Bogdanor, “Hung Parliaments and Proportional Representation”, in The Monarchy and the Constitution, Oxford: Clarendon Press, →ISBN, page 145:

- The likelihood of a hung parliament—that is, a parliament in which no single party enjoys an overall majority—is far greater today than it was, for example, in the 1950s. This is primarily because there are now more MPs from the minority parties.

- 1998 September, Tim Hames, Mark Leonard, “The Core Problem for the British Monarchy”, in Modernising the Monarchy (Arguments; 21), London: Demos, →ISBN, page 16:

- [I]f proportional representation were to be adopted for UK elections, the position could become even more complicated. In the event of a hung Parliament, which could be a regular occurrence under such a voting system, the monarch would have to nominate both the governing party and the prime minister and could face accusations of partisanship.

- 2015, Jennifer Menzies, Anne Tiernan, “Caretaker Conventions”, in Brian Galligan, Scott Brenton, editors, Constitutional Conventions in Westminster Systems: Controversies, Changes and Challenges, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, →ISBN, page 101:

- For Australia and the United Kingdom, hung parliaments, and the long transition period that accompany their formation, have been rare in the post-World War II period. […] Canada too began a cycle of hung parliaments from 2004, and this added complexity to what was traditionally a long transition period from election day to the first sitting of the new parliament […].

- 2017 June 9, Rajeev Syal, Alan Travis, “What is a hung parliament and what happens now?: The Conservatives have failed to win a majority but [Theresa] May – or her successor as Tory leader – will still try to form a government”, in The Guardian[1], London, archived from the original on 9 June 2017:

- We are heading for a hung parliament. The UK's first-past-the-post electoral system means balanced parliaments rarely happen in Britain, but it was the case following the 1974 election and most recently in 2010. In the case of a hung parliament, the leader of the party with the most seats is given the opportunity to try to form a government. This can take two forms: one option is a formal coalition with other parties, in which the coalition partners share ministerial jobs and push through a shared agenda. The other possibility is a more informal arrangement, known as "confidence and supply", in which the smaller parties agree to support the main legislation, such as a budget and Queen's speech put forward by the largest party, but do not formally take part in government.

Usage notes[edit]

This term is chiefly used in two-party systems, or in systems where there are two major political parties. In a multiparty system it is unusual that a single party would obtain a majority of the seats in the legislature.

Synonyms[edit]

Translations[edit]

parliament in which no single political party has an outright majority

|

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

hung parliament on Wikipedia.Wikipedia

hung parliament on Wikipedia.Wikipedia